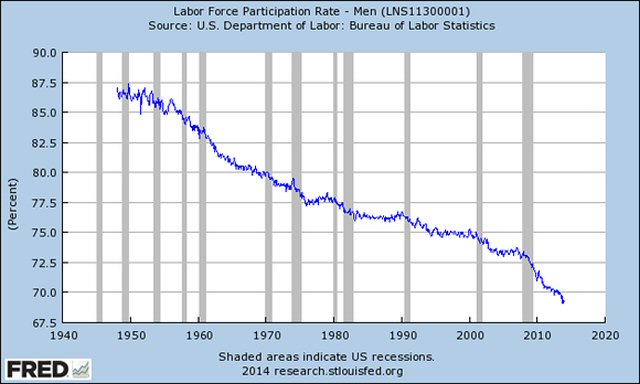

In the mid 1950s, nearly every man in his prime working years was in the labor force, a category that includes both those who are employed and those actively applying for jobs. Early in 1956 the “participation rate” for men ages 25 to 54 stood at 97.7%. By late 2012 it had declined to a post-war record low of 88.4%.

Where did they go? Some went into prison. Others are on disability or can’t find jobs in occupations that are now obsolete, exported, or taken over by women, who (still) get paid less for the same work.

The trend is especially pronounced among the less educated. As the available blue-collar jobs in manufacturing, production and other fields traditionally dominated by men without college diplomas declined, many were left behind. But men with college degrees are leaving, too. The participation rate of those older than 25 and holding at least a bachelor’s degree fell to 80.2% in May 2013, down from 87.2% in 1992.

The economic cycles since World War II have failed to stem this downward slide, even when the unemployment rate hit a 30-year low in the early 2000s. The Great Recession accelerated the trend, pushing the participation rate for men in their prime working years below 90% for the first time.

Here’s a breakdown of the reasons why men are dropping out of the labor force.

Prison

A growing number of men have served time in jail, which makes it much harder to be accepted for a job once they complete their sentences. 1.2% of white men and 9% of black men born just after World War II went to jail prior to 2004. In contrast, for those born 30 years later, the rates were 3.3% and 20.7% respectively.

Disability

More men have been pouring into the federal disability system, especially in recent years, when the Great Recession and its aftermath pushed up the national unemployment rate. According to data from the National Academy of Social Insurance, in 1982 around 1.9% of working-age men were receiving disability benefits. By 2012, that number had climbed to 3.1%. Once on the disability rolls, few people get off. Only 2.2% did so in the first quarter of 2013.

Lack of education

A few decades ago, men could graduate high school and make a decent living on a factory floor or at a construction job. As the labor market becomes more skilled, those guys are being left behind. For less than wealthy individuals, the already high (and increasing) cost of a college education that does not guarantee a job upon graduation means accepting responsibility for non-dischargeable debt, equal to or higher than the mortgage on a home. Social networks are full of tales alerting them to the consequences of being forced to accept minimum wage jobs: the despair of little or no disposable income that leaves them unable to compete for the affection of women who, incidentally, may earn far more than they.

Competition from women

According to data in Wayward Sons, in the 1960s more men than women were enrolling in and completing college. Women born in 1975 were roughly 17% more likely than their male counterparts to attend college and nearly 23% more likely to complete a four-year degree.

Obviously, many non-college men refuse to work in low-paying jobs. The decline of men in the labor force has broad, deep ramifications for families, taxpayers and the economy. Fewer employed men mean higher entitlements, reduced tax revenue, a potential for higher crime rates, and more unstable relationships with single-parent households. Perhaps the single most important consequence is that these unemployed adult men are also voters. Naturally they may favor candidates that believe that it is the government’s responsibility to see to it that well-paying, permanent jobs are plentiful.