June 10, 2018

Background

Israel is one of two (the other is Saudi Arabia) top allies of the United States, and as attested by the recent disarray in Canada, higher than its G-7 partners. Among the reasons for this preference are shared concerns over the two supporting pillars of the American economy: the petrodollar –the all-important reason for its (still) privileged position as the premiere reserve currency of the world- and the international bond market that nourishes America’s deficit-based fiscal policy. Should either pillar collapse, so would the American economy and its ability to support Israel. As it now stands, the U.S. has its hands full, and there’s no relief in sight. Not only is it in the midst of a profound demographic change that may in time fundamentally alter its political orientation, it’s burdened by a $21 trillion (and counting) debt, a decades-long trade deficit (no one knows how the looming trade wars with most of the world will evolve), and an unparalleled challenge from China, a country with a population four times larger and an economy growing two to three times faster. In addition, as of this writing, serious divisions already exist between Jewish Americans, who are predominately Democrats, and Israelis. In view of all this plus the fact that no country has ever won all its wars nor remained perpetually dominant, a pragmatic reexamination of the seemingly intractable Israel-Palestinian conflict seems in order.

Choices

The first choice is simple enough: do nothing, stay the course. This presumes that the U.S. will emerge victorious from all its confrontations, that American economic, military, diplomatic and political support for Israel will continue unabated and indefinitely, that Iran’s growing military prowess will soon be demolished, and –in the least sanguine of cases- that the will of the Palestinians will be broken. The alternative of course is to seek a peaceful and equitable solution based on the fundamental premise that Israelis and Palestinians have an inalienable right to live in peace in separate sovereign states within what today is known as Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. Obviously this is not new; many prominent leaders have failed. What is new is that breakthroughs in the solar/hydrogen/gravity/water nexus and desertification technologies have created a hitherto nonexistent window of opportunity to peacefully and permanently settle the problem. While there are risks and possible unintended consequences with either approach, the former is likely a direct path to war while the latter gives peace a chance.

Basic Assumptions

We begin by assuming that Israel’s non-negotiable aspirations include annexing the entire West Bank, retaining the Golan Heights (which is tangentially related but not a part of the Palestinian issue per se), permanent physical separation between Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, and Palestinian recognition that all of Jerusalem has been annexed and is now the capital of Israel. As for the Palestinians, we’ll assume their highest priority is to have a sovereign state immune from Israeli incursions, invasions, demolitions and blockades, the right to repatriate any and all Palestinians currently living abroad, and a desire to make East Jerusalem the capital of a Palestinian State.

Phases

This proposal envisions a series of time-defined phases to achieve the two-state solution. The cost of the project would require the materialization of financial donors. This is feasible.

Gaza

At best, there is considerable animosity in Gaza; at worst it is a breeding ground for hatred –on both sides of the fence. Therefore the first step should be to disengage and permanently separate Gazans and Israelis. One way to do so is to swap Gaza for an equivalent area around Eilat. Israel would acquire the entire Mediterranean coast; Gazans would get instant relief from the blockade plus a city with superior infrastructure adjacent to kindred Arabic-speaking neighbors in the Gulf of Aqaba. The new border between the Eilat region and Israel would be temporary, subject to change in conjunction with the West Bank phase.

The West Bank

The entire West Bank would be swapped for an area of equivalent size beginning at the northern boundary of the Eilat region and west of the Jordanian border north to the southwest corner of the Dead Sea. The configuration of the northern and western boundaries of the swapped area would be negotiated to take into account the security of Israel’s existing sensitive nuclear and military facilities. In the meantime, Israel would temporarily pay ground rent to the Palestinians for the former’s settlements in the West Bank, retroactively to the time they were built and ending when the West Bank swap is fully executed.

Water

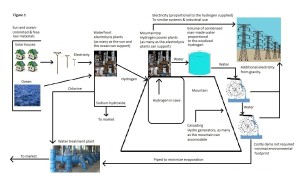

As the Palestinians would be getting a parched desert, this entire plan is predicated on the creation of a new adequate source of water. A sea level canal would be dug from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Dead Sea; solar power would be used to produce hydrogen from seawater; the hydrogen would be oxidized, and in conjunction with gravity would generate surplus electricity and manufacture pure water. Fossil fuels would not be required. The newly created water would be used to support a program of desertification as outlined in this Chinese project.

Jerusalem

Palestinians would have a right of access to the Dome of the Rock, as per current regulations; however their political capital would be any city except Jerusalem.