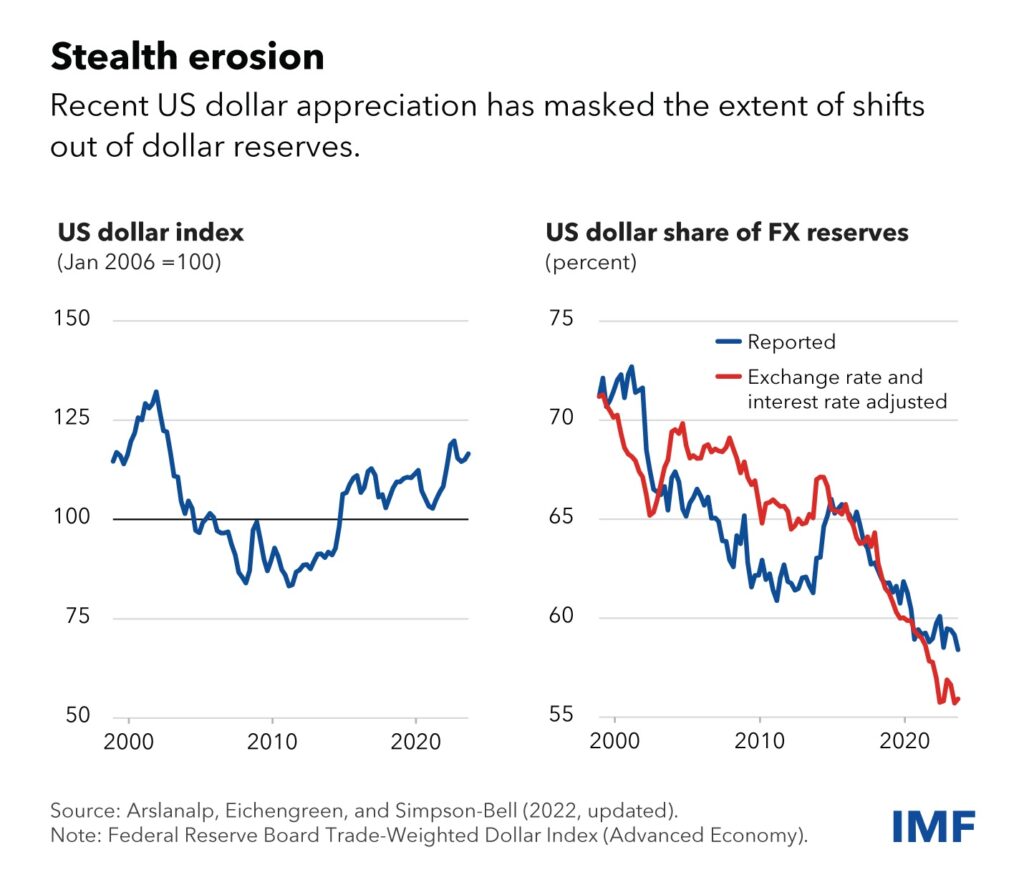

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the U.S. dollar share of global foreign exchange reserves declined from roughly 73% in 2000 to about 56% in 2020 despite the dollar’s continued appreciation during that period. Particularly noteworthy is the slope of the decline beginning in 2014, the year of the Ukrainian Revolution but prior to the Russian invasion and the subsequent sanctions from the U.S. and its allies. Importantly, the figures do not quantify the recent and projected expansion of BRICS, their shared goal to drop the dollar in international transactions, and the growing tensions between the U.S. and China over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

The reason for the apparent paradox of the dollar’s appreciation and its declining FX reserve status is that since 1974 the dollar has in effect been backed by oil. No other currency has enjoyed that privilege.

That status is under siege. In 2009 the head of the People’s Bank of China issued a white paper calling for a neutral reserve asset to replace the dollar-centric system. In addition, China, the world’s largest importer of oil, has also bought vast quantities of gold and begun to sell its hoard of U.S. Treasuries, hitherto one of the largest in the world. Then, in January 2023, Saudi Arabia openly declared that it was willing to sell oil in currencies other than the dollar, and in November of that year it sealed a currency swap deal with China. Time will tell how this saga will evolve. What is certain is that a new trend has emerged.

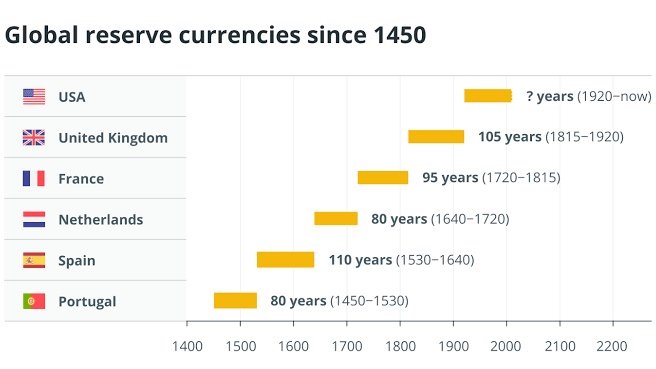

Beginning with the 15th Century countries whose currencies were the de facto FX global reserves also dominated the world. Three facts stand out: all unsuccessfully attempted to preserve that privilege, all were either Europeans or their progeny, and none have been able to reach the summit again.

The last time this happened, from the British pound to the U.S. dollar, was a peaceful succession. Today China, Russia, India, Brazil and Iran, among many others, are directly challenging the dollar’s dominance. And this is happening while Taiwan, Ukraine, and Israel/Palestine could at any time escalate into all-out war between the U.S. and Russia, or China, or both.

To put this in context, no one can win a nuclear war because life as we know it would cease to exist in less than one hour. The initial death toll would be in the many millions, followed by at least 5 billion due to nuclear winter. And yet, our leaders publicly specify the circumstances under which they would use these weapons. Their overt warnings imply that dominance is more important than survival, a contradiction in terms since their primary mission is to look after the well-being of their respective populations.

While nothing could undo the devastation of nuclear war, there is a way to prevent it: disarmament. However, that has prerequisites. One is to address the primeval feeling of helpless impotence, whether economic or military, or both, that occurs when a hostile power becomes dominant. Another, particularly as it pertains to the U.S., is to prevent the hyperinflation that would overwhelm its economy if and when foreign demand for dollars nosedives and they are repatriated. This of course would imply that paper dollars would no longer be accepted globally to settle international transactions. Before dismissing this thought as a chimera, recall the obvious antecedent. In the 19th Century Chinese goods, particularly tea, porcelain and silk were very popular in Great Britain. However, true to the Confucian ways, particularly their philosophy of self-sufficiency, China did not want to buy British goods. Furthermore, they demanded to be paid in silver, not paper money, for their exports. Earlier that century Spain had lost its American colonies. When that happened the river of silver it had been enjoying dried up, and since Spain had been spending upwards of 90% of its revenue in imported goods, many of them British, the latter lost one of its main sources of silver. As a result, Britain faced a shortage of it to pay the Chinese merchants. Its solution was to force China to legalize and import opium from Britain’s Indian colonies to redress the trade imbalance. Never before, or since, has one country forced another, at gunpoint, to have its population become addicted to a narcotic.

BRICS doesn’t have to use one of their national currencies to replace the dollar. All they have to do, when they’re good and ready and not before, is to stop accepting dollars as payment for their goods and services. If China did this by itself in the 19th Century, collectively they might do it too.

To say that this would usher in wholesale chaos would be a gross understatement. For the U.S., which is already saddled with immense and chronic current account and trade deficits, it would be an unprecedented catastrophe. And the European Union, which is closely linked to the American market and the dollar, would likely also be dragged into the swirl.