February 4, 2016

Henry Kissinger’s speech (original link to https://gorbachovfund.ru is broken) at the Gorbachev Fund in Moscow

From 2007 into 2009, Evgeny Primakov and I chaired a group composed of retired senior ministers, high officials, and military leaders from Russia and the United States, including some of you present here today. Its purpose was to ease the adversarial aspects of the U.S.-Russian relationship and to consider opportunities for cooperative approaches. In America, it was described as a Track II group, which meant it was bipartisan and encouraged by the White House to explore but not negotiate on its behalf. We alternated meetings in each other’s country. President Putin received the group in Moscow in 2007, and President Medvedev in 2009. In 2008, President George W. Bush assembled most of his National Security team in the Cabinet Room for a dialogue with our guests.

From 2007 into 2009, Evgeny Primakov and I chaired a group composed of retired senior ministers, high officials, and military leaders from Russia and the United States, including some of you present here today. Its purpose was to ease the adversarial aspects of the U.S.-Russian relationship and to consider opportunities for cooperative approaches. In America, it was described as a Track II group, which meant it was bipartisan and encouraged by the White House to explore but not negotiate on its behalf. We alternated meetings in each other’s country. President Putin received the group in Moscow in 2007, and President Medvedev in 2009. In 2008, President George W. Bush assembled most of his National Security team in the Cabinet Room for a dialogue with our guests.

All the participants had held responsible positions during the Cold War. During periods of tension, they had asserted the national interest of their country as they understood it. But they had also learned through experience the perils of a technology threatening civilized life and evolving in a direction which, in crisis, might disrupt any organized human activity. Upheavals were looming around the globe, magnified in part by different cultural identities and clashing ideologies. The goal of the Track II effort was to overcome crises and explore common principles of world order.

Evgeny Primakov was an indispensable partner in this effort. His sharp analytical mind combined with a wide grasp of global trends acquired in years close to and ultimately at the center of power, and his great devotion to his country refined our thinking and helped in the quest for a common vision. We did not always agree, but we always respected each other. He is missed by all of us and by me personally as a colleague and a friend.

I do not need to tell you that our relations today are much worse than they were a decade ago. Indeed, they are probably the worst they have been since before the end of the Cold War. Mutual trust has been dissipated on both sides. Confrontation has replaced cooperation. I know that in his last months, Evgeny Primakov looked for ways to overcome this disturbing state of affairs. We would honor his memory by making that effort our own.

At the end of the Cold War, both Russians and Americans had a vision of strategic partnership shaped by their recent experiences. Americans were expecting that a period of reduced tensions would lead to productive cooperation on global issues. Russian pride in their role in modernizing their society was tempered by discomfort at the transformation of their borders and recognition of the monumental tasks ahead in reconstruction and redefinition. Many on both sides understood that the fates of Russia and the U.S. remained tightly intertwined. Maintaining strategic stability and preventing the spread of weapons of mass destruction became a growing necessity, as did the building of a security system for Eurasia, especially along Russia’s long periphery. New vistas opened up in trade and investment; cooperation in the field of energy topped the list.

Regrettably, the momentum of global upheaval has outstripped the capacities of statesmanship. Evgeny Primakov’s decision as Prime Minister, on a flight over the Atlantic to Washington, to order his plane to turn around and return to Moscow to protest the start of NATO military operations in Yugoslavia was symbolic. The initial hopes that the close cooperation in the early phases of the campaign against al-Qaida and the Taliban in Afghanistan might lead to partnership on a broader range of issues weakened in the vortex of disputes over Middle East policy, and then collapsed with the Russian military moves in the Caucasus in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014. The more recent efforts to find common ground in the Syria conflict and to defuse the tension over Ukraine have done little to change the mounting sense of estrangement.

The prevailing narrative in each country places full blame on the other side, and in each country there is a tendency to demonize, if not the other country, then its leaders. As national security issues dominate the dialogue, some of the mistrust and suspicions from the bitter Cold-War struggle have reemerged. These feelings have been exacerbated in Russia by the memory of the first post-Soviet decade when Russia suffered a staggering socio-economic and political crisis, while the United States enjoyed its longest period of uninterrupted economic expansion. All this caused policy differences over the Balkans, the former Soviet territory, the Middle East, NATO expansion, missile defense, and arms sales to overwhelm prospects for cooperation.

Perhaps most important has been a fundamental gap in historical conception. For the United States, the end of the Cold War seemed like a vindication of its traditional faith in inevitable democratic revolution. It visualized the expansion of an international system governed by essentially legal rules. But Russia’s historical experience is more complicated. To a country across which foreign armies have marched for centuries from both East and West, security will always need to have a geopolitical, as well as a legal, foundation. When its security border moves from the Elbe 1,000 miles east towards Moscow, Russia’s perception of world order will contain an inevitable strategic component. The challenge of our period is to merge the two perspectives—the legal and the geopolitical—in a coherent concept.

In this way, paradoxically, we find ourselves confronting anew an essentially philosophical problem. How does the United States work together with Russia, a country which does not share all its values but is an indispensable component of the international order? How does Russia exercise its security interests without raising alarms around its periphery and accumulating adversaries? Can Russia gain a respected place in global affairs with which the United States is comfortable? Can the United States pursue its values without being perceived as threatening to impose them? I will not attempt to propose answers to all these questions. My purpose is to encourage an effort to explore them.

Many commentators, both Russian and American, have rejected the possibility of the U.S. and Russia working cooperatively on a new international order. In their view, the United States and Russia have entered a new Cold War.

The danger today is less a return to military confrontation than the consolidation of a self-fulfilling prophecy in both countries. The long-term interests of both countries call for a world that transforms the contemporary turbulence and flux into a new equilibrium which is increasingly multipolar and globalized.

The nature of the turmoil is in itself unprecedented. Until quite recently, global international threats were identified with the accumulation of power by a dominating state. Today threats more frequently arise from the disintegration of state power and the growing number of ungoverned territories. This spreading power vacuum cannot be dealt with by any state, no matter how powerful on an exclusively national basis. It requires sustained cooperation between the United States and Russia, and other major powers. Therefore the elements of competition, in dealing with the traditional conflicts in the interstate system, must be constrained so that the competition remains within bounds and creates conditions which prevent a recurrence.

There are, as we know, a number of divisive issues before us, Ukraine or Syria as the most immediate. For the past few years, our countries have engaged in episodic discussions of such matters without much notable progress. This is not surprising, because the discussions have taken place outside an agreed strategic framework. Each of the specific issues is an expression of a larger strategic one. Ukraine needs to be embedded in the structure of European and international security architecture in such a way that it serves as a bridge between Russia and the West, rather than as an outpost of either side. Regarding Syria, it is clear that the local and regional factions cannot find a solution on their own. Compatible U.S.-Russian efforts coordinated with other major powers could create a pattern for peaceful solutions in the Middle East and perhaps elsewhere.

Any effort to improve relations must include a dialogue about the emerging world order. What are the trends that are eroding the old order and shaping the new one? What challenges do the changes pose to both Russian and American national interests? What role does each country want to play in shaping that order, and what position can it reasonably and ultimately hope to occupy in that new order? How do we reconcile the very different concepts of world order that have evolved in Russia and the United States—and in other major powers—on the basis of historical experience? The goal should be to develop a strategic concept for U.S.-Russian relations within which the points of contention may be managed.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, I perceived international relations as an essentially adversarial relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union. With the evolution of technology, a conception of strategic stability developed that the two countries could implement, even as their rivalry continued in other areas. The world has changed dramatically since then. In particular, in the emerging multipolar order, Russia should be perceived as an essential element of any new global equilibrium, not primarily as a threat to the United States.

I have spent the greater part of the past seventy years engaged in one way or another in U.S.-Russian relations. I have been at decision centers when alert levels have been raised, and at joint celebrations of diplomatic achievement. Our countries and the peoples of the world need a more durable prospect.

I am here to argue for the possibility of a dialogue that seeks to merge our futures rather than elaborate our conflicts. This requires respect by both sides of the vital values and interest of the other. These goals cannot be completed in what remains of the current administration. But neither should their pursuits be postponed for American domestic politics. It will only come with a willingness in both Washington and Moscow, in the White House and the Kremlin, to move beyond the grievances and sense of victimization to confront the larger challenges that face both of our countries in the years ahead.

From 2007 into 2009, Evgeny Primakov and I chaired a group composed of retired senior ministers, high officials, and military leaders from Russia and the United States, including some of you present here today. Its purpose was to ease the adversarial aspects of the U.S.-Russian relationship and to consider opportunities for cooperative approaches. In America, it was described as a Track II group, which meant it was bipartisan and encouraged by the White House to explore but not negotiate on its behalf. We alternated meetings in each other’s country. President Putin received the group in Moscow in 2007, and President Medvedev in 2009. In 2008, President George W. Bush assembled most of his National Security team in the Cabinet Room for a dialogue with our guests.

From 2007 into 2009, Evgeny Primakov and I chaired a group composed of retired senior ministers, high officials, and military leaders from Russia and the United States, including some of you present here today. Its purpose was to ease the adversarial aspects of the U.S.-Russian relationship and to consider opportunities for cooperative approaches. In America, it was described as a Track II group, which meant it was bipartisan and encouraged by the White House to explore but not negotiate on its behalf. We alternated meetings in each other’s country. President Putin received the group in Moscow in 2007, and President Medvedev in 2009. In 2008, President George W. Bush assembled most of his National Security team in the Cabinet Room for a dialogue with our guests.

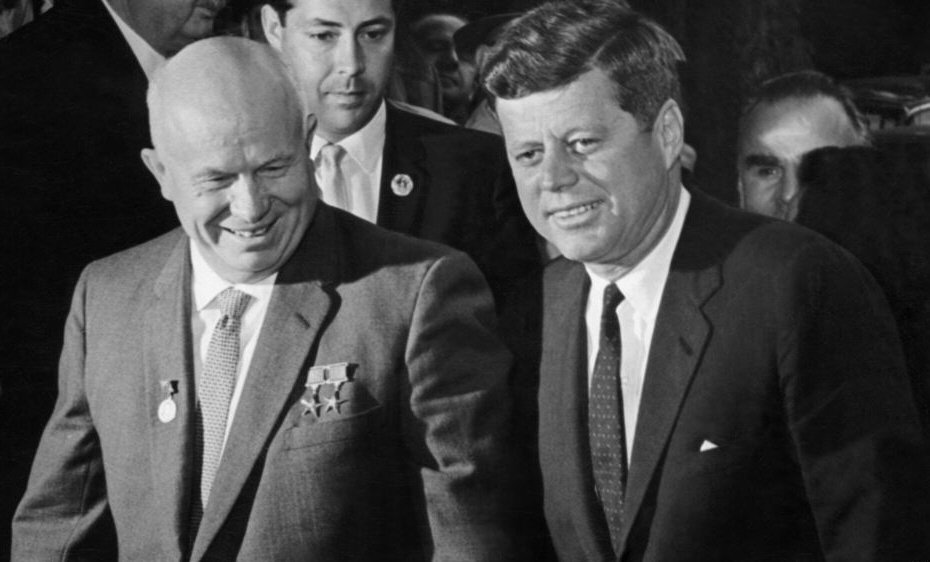

“I can’t believe that this world can go on beyond our generation and on down to succeeding generations with this kind of weapon on both sides poised at each other without someday some fool or some maniac or some accident triggering the kind of war that is the end of the line for all of us. And I just think of what a sigh of relief would go up from everyone on this earth if someday–and this is what I have–my hope, way in the back of my head–is that if we start down the road to reduction, maybe one day in doing that, somebody will say, ‘Why not all the way? Let’s get rid of all these things’.”

“I can’t believe that this world can go on beyond our generation and on down to succeeding generations with this kind of weapon on both sides poised at each other without someday some fool or some maniac or some accident triggering the kind of war that is the end of the line for all of us. And I just think of what a sigh of relief would go up from everyone on this earth if someday–and this is what I have–my hope, way in the back of my head–is that if we start down the road to reduction, maybe one day in doing that, somebody will say, ‘Why not all the way? Let’s get rid of all these things’.”