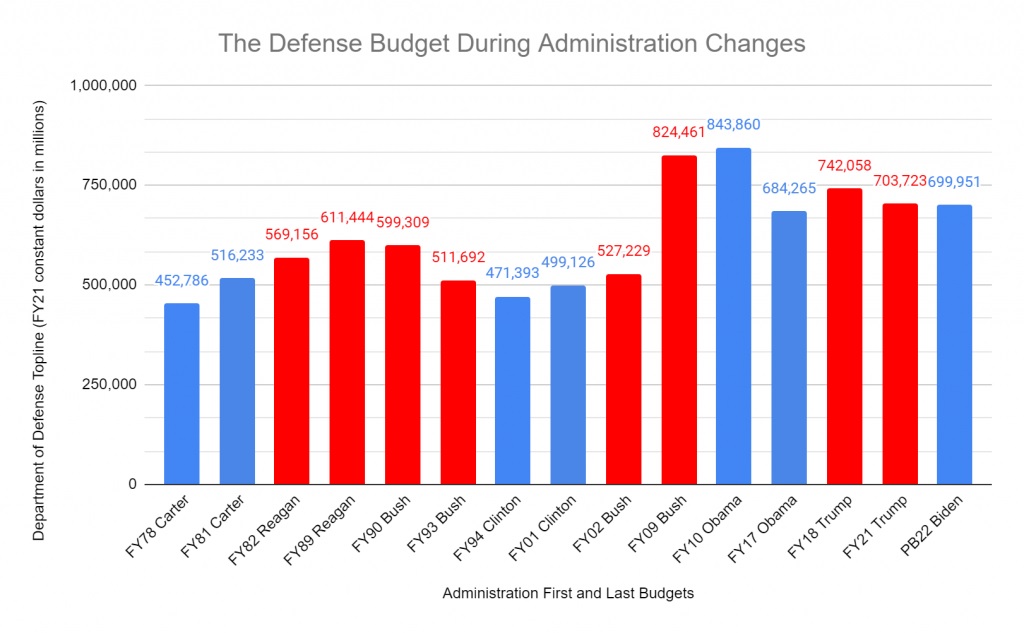

Note: On March 11, 2024, the Biden-Harris Administration submitted to Congress a proposed Fiscal Year (FY) 2025 budget request of $849.8 billion for the Department of Defense (DoD), consistent with the caps approved by Congress under the Financial Responsibility Act (FRA) of 2023. On August 1, 2024 the Senate Appropriations Committee approved its fiscal 2025 defense spending bill, funding the Defense Department at $852.2 billion. Though approved unanimously, the bill still has to be reconciled with the House’s version of the Pentagon funding legislation, which authorized $833 billion in total funding. The proposed 3.3% increase in defense spending suggests that the bipartisan agreement on spending caps might be falling apart.

Hydrogen as a Peacemaker

The idea of using solar (or geothermal) energy and seawater to mass-produce green hydrogen by electrolysis, burn it and add gravity to generate a surplus of electricity and freshwater, even far from shore (which desalination cannot do), is feasible, practical and necessary. Indeed, it is a seismic proposal, in more ways than one. For starters, the pertinent raw materials –solar energy, seawater and gravity- are in the public domain, easily accessible and, except for landlocked nations, which have no direct access to the ocean, universally available. As a result, it would be extraordinarily difficult for anyone to organize a global cartel with the power to allocate production quotas of hydrogen and to set its price. Gradually the scheme would make nuclear fission and fossil fuels obsolete, dramatically increase the supply of hydrogen needed to build a widespread, reliable network of hydrogen automobile pumping stations, modernize the electric power industry, stop the wholesale dumping of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, end the real estate crisis for the working class, and create millions of non-temporary, well-paying construction and energy jobs that cannot be outsourced.

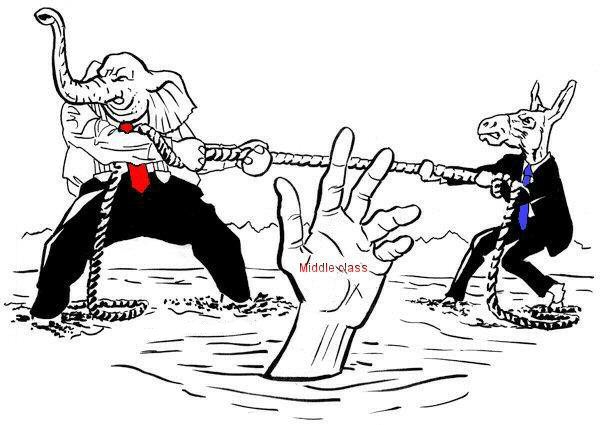

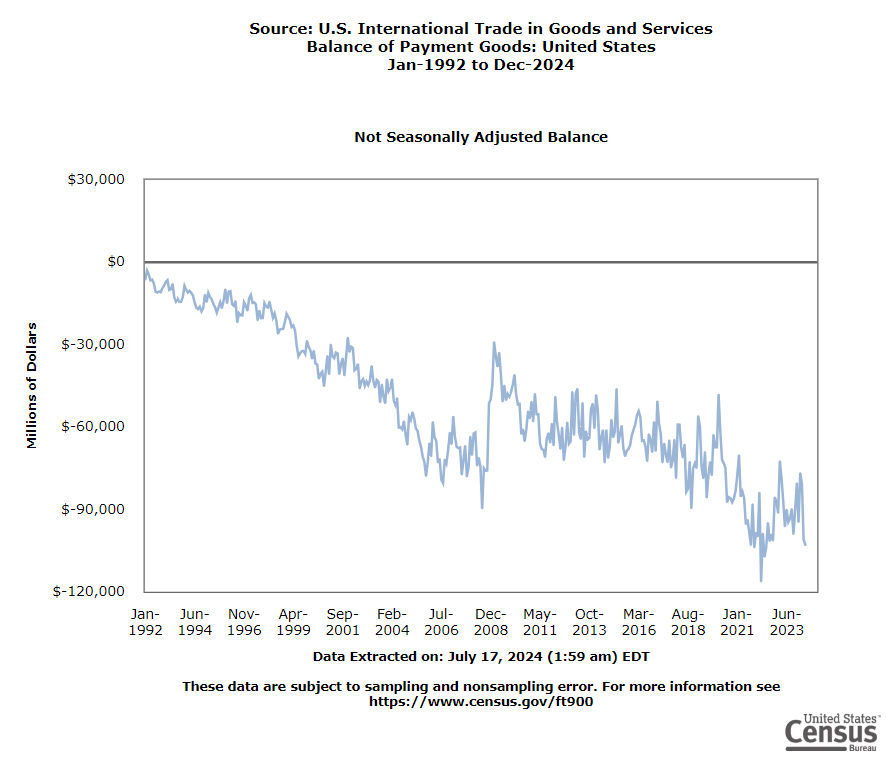

Since oil is the main support pillar of the value of the dollar and the demand for oil will at some point collapse, it follows that the dollar needs to replace the oil mainstay. Accordingly, today’s essay looks at the dollar in light of the enormous burden of chronic current account and trade deficits and the necrotic inability of our elected leaders to come to its rescue.

BRICS countries don’t have to promote one of their national currencies to global reserve status. All they have to do, when they’re good and ready, is to stop accepting dollars as payment for their goods and services. If China did this by itself in the 19th Century, collectively they might do it too.

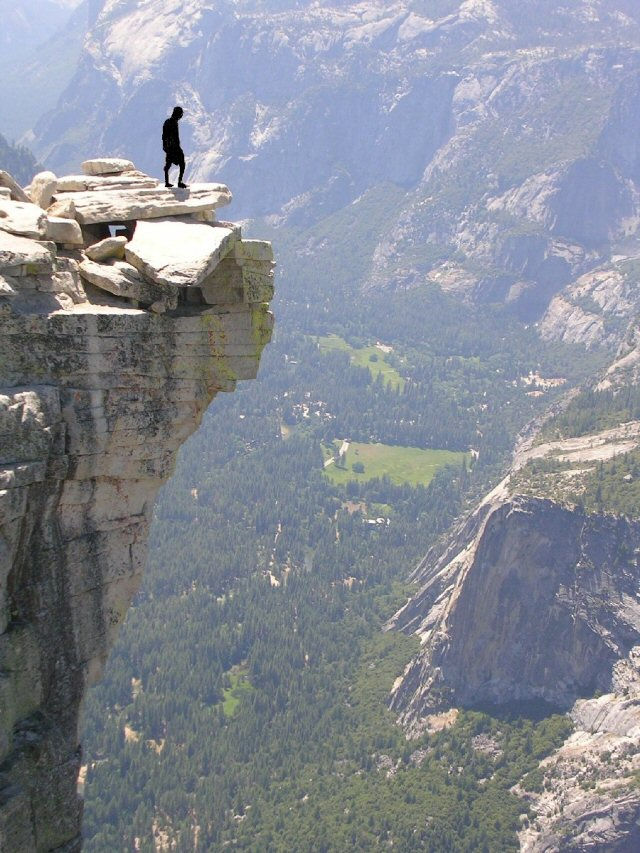

To say that this would usher in wholesale chaos would be a gross understatement. For the U.S., it would be an ominous event. And the European Union, which is closely linked to the American market and the dollar, would be dragged into the vortex. In other words, countermeasures must be taken to preclude the global economy from falling into the abyss.

It makes no sense to peg any currency to gold; the supply is finite, there are 8 billion people (and counting) in the world, and it just doesn’t work. Green hydrogen, which is renewable, fits the bill. it’s high time to let it determine the value of all currencies.

Status of the Dollar

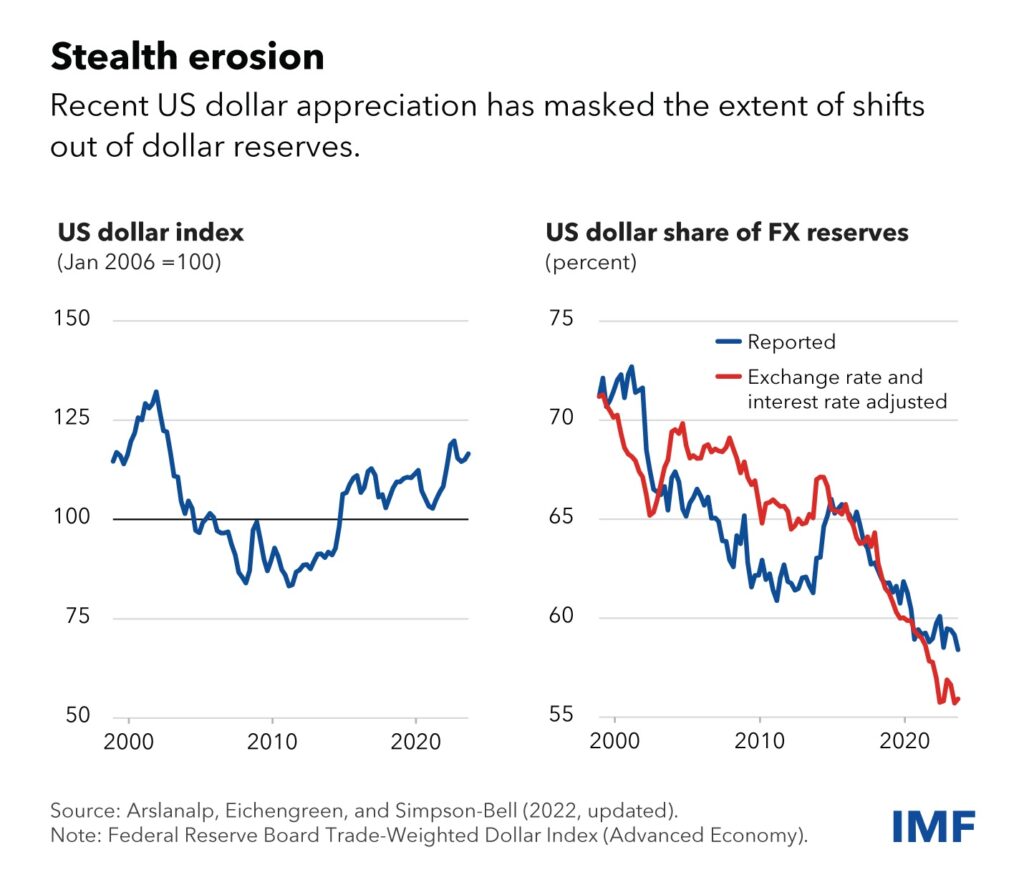

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the U.S. dollar share of global foreign exchange reserves declined from roughly 73% in 2000 to about 56% in 2020 despite the dollar’s continued appreciation during that period. Particularly noteworthy is the slope of the decline beginning in 2014, the year of the Ukrainian Revolution but prior to the Russian invasion and the subsequent sanctions from the U.S. and its allies. Importantly, the figures do not quantify the recent and projected expansion of BRICS, their shared goal to drop the dollar in international transactions, and the growing tensions between the U.S. and China over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

The reason for the apparent paradox of the dollar’s appreciation and its declining FX reserve status is that since 1974 the dollar has in effect been backed by oil. No other currency has enjoyed that privilege.

That status is under siege. In 2009 the head of the People’s Bank of China issued a white paper calling for a neutral reserve asset to replace the dollar-centric system. In addition, China, the world’s largest importer of oil, has also bought vast quantities of gold and begun to sell its hoard of U.S. Treasuries, hitherto one of the largest in the world. Then, in January 2023, Saudi Arabia openly declared that it was willing to sell oil in currencies other than the dollar, and in November of that year it sealed a currency swap deal with China. Time will tell how this saga will evolve. What is certain is that a new trend has emerged.

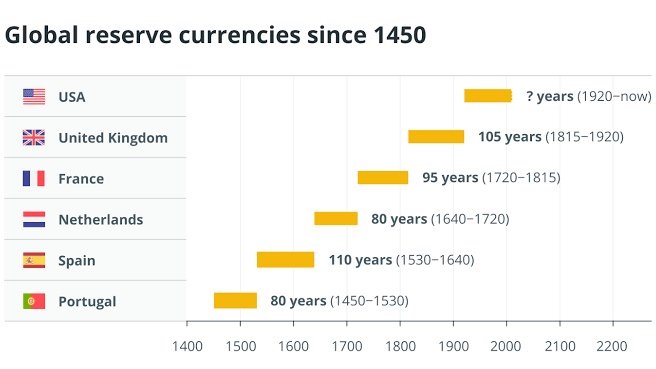

Beginning with the 15th Century countries whose currencies were the de facto FX global reserves also dominated the world. Three facts stand out: all unsuccessfully attempted to preserve that privilege, all were either Europeans or their progeny, and none have been able to reach the summit again.

The last time this happened, from the British pound to the U.S. dollar, was a peaceful succession. Today China, Russia, India, Brazil and Iran, among many others, are directly challenging the dollar’s dominance. And this is happening while Taiwan, Ukraine, and Israel/Palestine could at any time escalate into all-out war between the U.S. and Russia, or China, or both.

To put this in context, no one can win a nuclear war because life as we know it would cease to exist in less than one hour. The initial death toll would be in the many millions, followed by at least 5 billion due to nuclear winter. And yet, our leaders publicly specify the circumstances under which they would use these weapons. Their overt warnings imply that dominance is more important than survival, a contradiction in terms since their primary mission is to look after the well-being of their respective populations.

While nothing could undo the devastation of nuclear war, there is a way to prevent it: disarmament. However, that has prerequisites. One is to address the primeval feeling of helpless impotence, whether economic or military, or both, that occurs when a hostile power becomes dominant. Another, particularly as it pertains to the U.S., is to prevent the hyperinflation that would overwhelm its economy if and when foreign demand for dollars nosedives and they are repatriated. This of course would imply that paper dollars would no longer be accepted globally to settle international transactions. Before dismissing this thought as a chimera, recall the obvious antecedent. In the 19th Century Chinese goods, particularly tea, porcelain and silk were very popular in Great Britain. However, true to the Confucian ways, particularly their philosophy of self-sufficiency, China did not want to buy British goods. Furthermore, they demanded to be paid in silver, not paper money, for their exports. Earlier that century Spain had lost its American colonies. When that happened the river of silver it had been enjoying dried up, and since Spain had been spending upwards of 90% of its revenue in imported goods, many of them British, the latter lost one of its main sources of silver. As a result, Britain faced a shortage of it to pay the Chinese merchants. Its solution was to force China to legalize and import opium from Britain’s Indian colonies to redress the trade imbalance. Never before, or since, has one country forced another, at gunpoint, to have its population become addicted to a narcotic.

BRICS doesn’t have to use one of their national currencies to replace the dollar. All they have to do, when they’re good and ready and not before, is to stop accepting dollars as payment for their goods and services. If China did this by itself in the 19th Century, collectively they might do it too.

To say that this would usher in wholesale chaos would be a gross understatement. For the U.S., which is already saddled with immense and chronic current account and trade deficits, it would be an unprecedented catastrophe. And the European Union, which is closely linked to the American market and the dollar, would likely also be dragged into the swirl.

Egalitarian Ancient Maya

“In the Early Preclassic, prior to the emergence of civilization, Maya society was basically egalitarian. As ethnographic studies of the Chiapas highlands have shown, contemporary Maya communities usually are organized along similar lines. The community of Zinacantan, for instance, is organized around an egalitarian cargo system, whereby the positions of political and religious authority are held for one-year terms by male officeholders accompanied by their wives (who also share duties), and the officeholders rotate from one position to another. By taking office once every few years, each individual advances in the community hierarchy with age, and the positions of highest authority are thus held by the elders of society. In such a system all levels of power are shared, and there is no permanent ruling class. A similar system may have operated among the ancient Maya, perhaps during the earliest time periods, perhaps also as a basic organizational framework for small communities in later centuries. In either case, one may assume that beyond the basic lineage organization, people in rural residential clusters held rotating political and religious offices in the local agricultural villages.”

The Ancient Maya, Robert J. Sharer

Cinnabar, Mercury, and the Ancient Maya

It is known that ordinary ancient Maya had very few personal possessions. They cultivated the land with simple tools and lived in huts similar to the ones still used by their descendants. The ruling class, kings, nobility, priests, lived rather extravagantly in palaces. The kings claimed to be gods or representatives of gods, and had complete control of whatever was written on monuments and possibly in many of the bark paper books, a virtual monopoly of the only medium of mass-communication. Kings and priests supervised the scribes when they wrote, and, since writing was limited to a small percentage of the population, it was rather risky for scribes to write anything having to do with dissent as they could be exposed. Nevertheless, if they ever did choose to risk death, their uncensored works are now lost.

The claim of divinely anointed dynasties legitimized and perpetuated the power of the ruling classes. Commoners everywhere were led to believe that in exchange for yanking the beating hearts of captured enemies, the gods advised only their legitimate kings on anything essential to the well-being and survival of the polities, from matters of rain and agriculture to issues of war and peace. This myth was gradually exposed at the end of the late classical period, when a devastating drought lasting two-hundred years occurred. The deeply religious Cholan-speaking Maya in the Petén jungle depended on abundant, predictable rain not just for drinking and agriculture, but for transportation as well. The great river systems draining this vast area, principally the Usumancita and Motagua, were the easiest, most effective means of conducting commerce among the many polities located along or near their banks as well as with foreign, distant lands that supplied critical commodities not locally available. In their eyes, a disaster of this length and magnitude meant either that the kings were no longer able to intercede with the gods, or that they never could; either way, they lost their legitimacy.

The trail of cinnabar is undeniable evidence that, because of their location and geography, both Yucatecs and Cholans were maritime traders. Recent intense excavations in Cholan ruins, such as Copán, Palenque, Yaxchilán, and others, reveal its widespread availability. Cinnabar was used in many ways, including pottery, writing, textile dying, and most importantly, burials. This fixation -one can almost call obsession- with cinnabar was not because people were particularly fond of its color, or because they necessarily were unaware of alternate materials to produce the same shades of red. As with other distant and unrelated cultures such as China and Egypt, the Maya thought that cinnabar had mystical properties.

The Maya believed that after burial, bodies could resurrect and search for its immortal soul that had departed at death. Left untreated, they would roam the countryside at night, and, unsuccessful in their search, would forcibly wrench a soul from the living to replace their own. Terrified with the undead, people stayed home after dark, hoping that the measures they had undertaken to prevent this nightmare would suffice. They would place a heavy rock, lid, or boulder to seal a tomb, which, it was hoped, would stop the undead from emerging. They would also apply a heavy coat of cinnabar to the body. When it inevitably resurrected, the cinnabar would make the deceased accept the fact that it was dead and that its soul was gone forever. The corpse would have peace and leave the living alone. Cinnabar, therefore, implicitly invoked the protection of the Benefactor in whatever use it was involved with, and explains its heavy and widespread geographic and demographic use. When one wrote hieroglyphs about the gods, cinnabar reverently formalized the serious, faithful nature of what was said. When one wore garments with cinnabar one identified with the gods, preempting any possibility that evil spirits from Xibalbá (the underworld) might attempt any harm. Cinnabar, therefore, was fundamental, essential, vital. The king said so; the priests concurred.

The absence of local cinnabar mines combined with its widespread availability implies that an efficient, elaborate distribution network must have existed. Lacking beasts of burden, rivers were the freeways of the day. Slaves powered the ships on whose backs merchants and entrepreneurs traded furiously to generate the income with which to pay for the cinnabar.

It is known that there were –and still are- substantial deposits of cinnabar and obsidian at Pinal de Amoles and Sierra Gorda, north of modern Quéretaro City, in central Mexico. The Olmecs conducted intense mining operations and supplied Teotihuacán and El Tajín del Totonacapan. However, the most intense mining took place toward the Terminal Classic period and the beginning of the Post-Classic, a period which coincided with the highest degree of activity in the Cholan areas to the south. Teotihuacán, a great cultural, military, and commercial node northwest of today’s Mexico City, supplied central Mexico and the Maya-speaking Teenek (Huastecs) living along the Gulf Coast in modern day Tamaulipas and Veracruz States with cinnabar. It was here that the great ocean-going pirogues –

galley-sized canoes used by coastal dwelling peoples in the Caribbean- owned and supervised by Cholan merchants but powered by captured slaves, came to pick up vast amounts of cinnabar and rare types of obsidian bound for the rest of the Mayan realm, and to deliver much prized tropical goods such as quetzal and macaw feathers, skins, seashells, and medicines heading for the Mexican plateau. The trade was vital to the economies of both areas. Entire urban centers were devoted to the mining of cinnabar and obsidian in Querétaro State, such as Ranas of San Joaquín and Toluquilla of Caderyta de Montes. And in Maya polities, cinnabar helped the ruling class maintain and perpetuate its legitimacy. In both areas the powerful wealthy upper classes benefited the most because only they could afford to hoard the goods that defined and perpetuated a growing wealth inequality.

The evidence of this connection between Teotihuacán and Copán in today’s western Honduras, distant as they are from each other, is confirmed by the archeological and epigraphic record. Glyphs related to the founder of the Copán dynasty, K’imich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ (Great Sun, Green Quetzal Macaw) make reference to his association with Teotihuacán at the time of his accession to the throne on September 6, 426 AD, and there are reasons to believe his attire resembled that of contemporary Teotihuacán (Stuart, 2004). Except for a brief period, this association was maintained unbroken throughout the Classical Period of the Copán Dynasty. In conclusion, as previously stated, the physical presence of cinnabar inside the Copan tombs on the one hand, and the existence of mines in Queretaro at the other end of Mesoamerica on the other, conclusively prove that this commerce did in fact take place.

Cinnabar is not holy water, and it certainly is not an innocuous, harmless compound. Its mercury content is in fact highly toxic, the degree to which is only now beginning to be fully understood. A growing number of studies document the human toll: children exposed to mercury are slower to walk and talk and may be more susceptible to autism and attention deficit disorders. Adults can suffer memory loss, nerve damage and fatigue.